Go to the next Chapter»

Welcome to the beginning of I wish I could tell Mum.

It’s just after 9 pm on a Tuesday in October 2024. I’m cleaning up the kitchen after dinner when the familiar ping of a text message bounces at me from across the kitchen. It’s a jarring sound at that time of night. My brain instantly jumps to thoughts of ‘oh shit, what’s happened?’

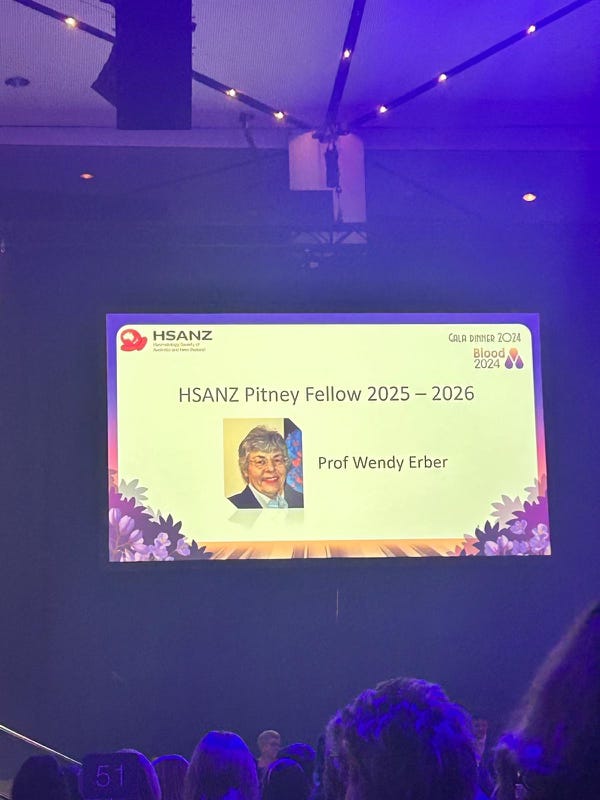

I stop what I’m doing and reach for the phone. It’s my Auntie Wendy in Perth. That relaxes me slightly - it's early on the West Coast. Her message is a photo of a slide projected onto a large screen in what I imagine to be a convention centre or hotel ballroom. Blood 2024. HSANZ Pitney Fellow 2025-26. Professor Wendy Erber. Wendy, a world-renowned Haematologist, has won a travelling fellowship that will enable her to further one of her passions - the education of haematology trainees. The final sentence of her message read ‘I wish I could tell Mum’.

That single sentence was the beginning of my path to writing this book.

Wendy’s Mum, Ilse, is in her 90s and has advanced-stage dementia. Wendy visits her at her care home each week despite knowing that Ilse doesn't recognise her. Wendy has lost the Mum she always knew. She may bear a physical resemblance, but in so many other ways, she is a different person. It would have been the most normal thing in the world for Wendy to share the news and excitement of her award with Ilse, but it’s no longer possible.

Dementia has stolen that moment, and so many others, from them.

Reading the message, my emotions skipped instantly from pride and excitement to a gut-wrenching sense of sadness. My heart, quite literally, hurt. I couldn't help but reflect on all of the moments in my life where my first instinct has been, and still is, to call my Mum. It’s the big moments and small, mundane things that happen on a given day that remind me of her. Everything from ‘Have you watched the new series of The Parisian Agency yet?’ to ‘I just cooked that recipe you sent me (and my version isn't as good as yours)’ or ‘I just signed a new client that I’m super excited about’, to ‘the dog did the funniest thing’.

In reading that one line in Wendy’s text, something hit me hard. A desire to share the impact of the lost moments, the changed relationships and families permanently altered by a parent’s dementia diagnosis.

This book is designed to share the perspectives of those of you who know what it is to grieve the loss of a parent twice. To honour the stories from your families and allow the rest of us to see inside the experience of caring for your Mum or Dad. I hope that in some small way, the telling of these stories will help you feel less alone.

For those of us without personal experience, it’s a chance to learn, to better understand and find ways to help and support our friends and neighbours who are involved in the care of one of the more than 57 million people living with dementia around the world.

I hope it helps.